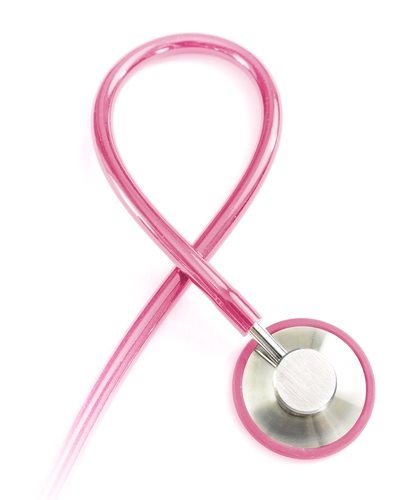

Can companies patent the genes that cause some types of breast cancer, so that only they can perform the tests for these genes? The Federal Circuit has said yes—twice—but their decision is being appealed. The case, started by the ACLU in 2009, may wind up back in front of the Supreme Court again in 2013 if the court grants certiorari.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 were two of the first genes to be identified in causing breast cancer. Myriad Genetics and the University of Utah Research Foundation obtained patents on these two genes, and they were the only entities that were allowed to license tests that could detect the presence or absence of the genes. These patents were rigorously enforced, leading many researchers to halt research on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes due to fears of being sued for patent infringement.

Myriad and the University of Utah Research Foundation even controlled the ability of researchers to look at the genes and create their own testing protocols. Patent law has long held, even since before the beginnings of the United States, that patents were not available on “products of nature.” The ACLU interpreted this to mean that the patent on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 was in violation of existing patent law, and they sued in federal district court.

The district court ruled at trial that the patents were illegal, but the appeals court reversed. The Supreme Court first looked at this issue two years ago and sent the case back to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, saying that it needed to change the way it was looking at the patents. In September of 2012, the Federal Court of Appeals ruled once again that the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene patents did not violate United States law.

The suit is being filed on behalf of several women with the genetic mutation, including women who were unable to find out about their genetic mutations for some time due to the extremely high cost of testing. At the time when the lawsuit was filed, testing for the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes could cost more than $4,000.

While the Court of Appeals ruled against the ACLU about the specific patents on the genes, there was a silver lining for people hoping for better access to testing in the future. The Court of Appeals also ruled that any patents on methods for comparing the genes to “wild-type” genes were not in fact legal according to United States patent and trademark law.

The Appeals Court based its ruling on the idea that once the genes being tested are reproduced in a laboratory and divorced from their constituent chromosomes, they are no longer “products of nature” but rather patentable objects of scientific study. The court said in its decision that if the United States Congress wanted to, it could constitutionally alter patent law in order to forbid the patenting of specific isolated genes, but that no such laws had been passed by Congress.

Sources: uscourts.gov, aclu.org